Residential Property Tax Discrimination in Atlanta, GA

Abstract

Jim Crow laws targeted African American neighborhoods for higher property taxes. In the 1950s and most of 1960s this accelerated to encourage black migration out of the south. Reforms in the 1970s and 1980s attempted to reverse this. Several works using public tax assessment-to-sales price records have found the bias disappeared, including (Makovi, 2022) who examined Atlanta where controversy over taxation had been contentious until reforms in 1991. Yet Jim Crow era rules did not include square footage in public property descriptions in order to create obstacles to challenge assessments. It is also difficult to locate the actual real estate tax charged to an owner as these have to be extracted one by one.

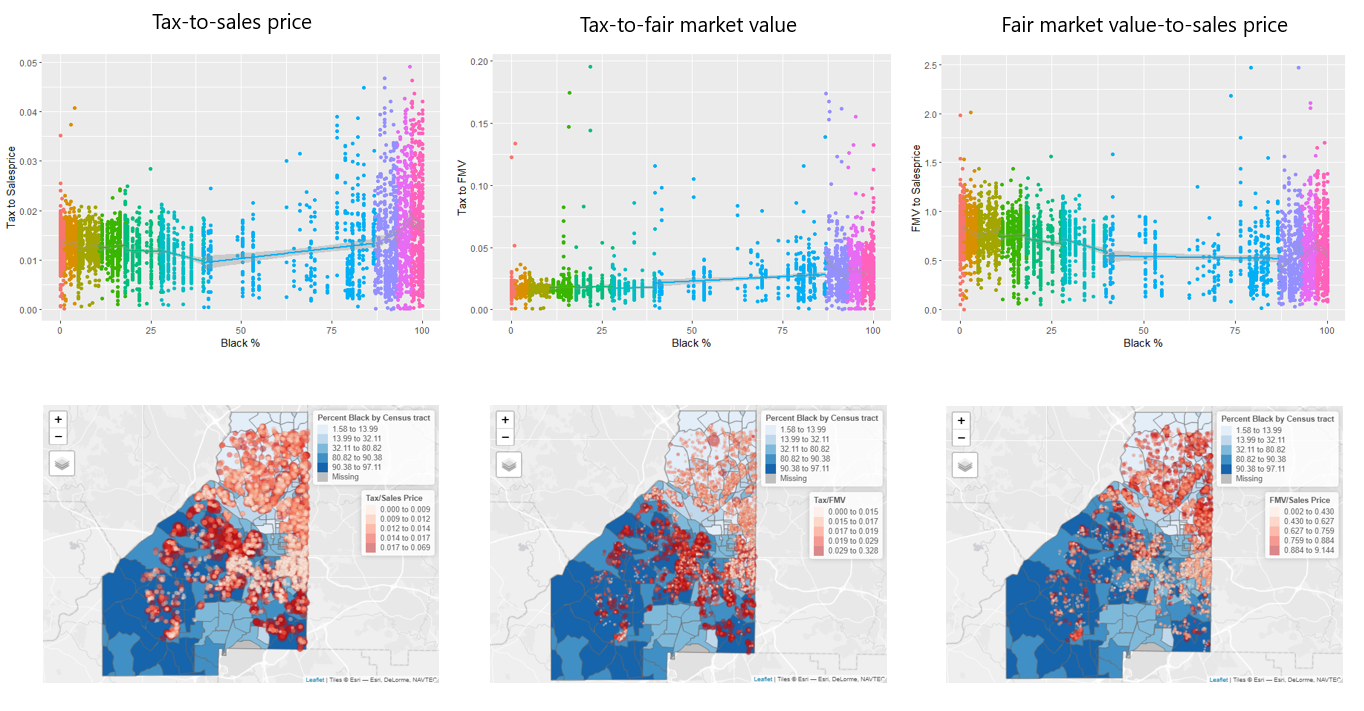

Using block group-level demographic data and updated housing characteristics, such as square footage, we compare actual property taxes-to-sales price and tax-to-assessment to specific property sales in 2015 and 2016 across Atlanta. We also find no bias in tax assessment-to-sales price, yet find a persistent and significant difference in tax charged-to-sales price and tax charged-to-assessment that discriminates against African Americans. Our results are robust even after sorting households in submarkets that are distinct in their income and demographics; this indicates the systemic over-taxation remains even within predominantly low income and African American neighborhoods.

Though Fulton County, in which nearly all of Atlanta lies, conducts assessments, and city leaders and many county officials have included some of the leading lights in the civil rights movement. Yet these institutional legacies of data strategically withheld or made extremely difficult to extract from public record during the Jim Crow era have proven persistent in their impacts on African Americans.